The Witches and Wakefields of Pendle Hill

A trip to Lancashire dedicated to my ancestors and the wonderful world of witches...

I know it has been a while since my last post - thank you all so much for your patience!

The last few weeks have been very intense, with several life-altering decisions being made. It’s exciting, but more than a little daunting at the same time…

Thankfully, I was able to enjoy a few days amidst Lancashire’s rolling hills. Filled with incredible history, invigorating walks, magical views, and glorious sunshine (for once!), my trip to Lancashire was the perfect way to unwind.

I have a strong personal connection to this part of England, as my paternal ancestors lived and worked around the border between Lancaster and Yorkshire. Whilst researching my family tree, I discovered that my paternal great-great-grandparents were buried in a small Yorkshire village called Greenhow.

Nestled high up within the Yorkshire Dales and centred around the highest church in the country, Greenhow is a rural haven with magnificent views across the rugged landscape. It was a bit of a trek to get there, which gives an insight into how isolated life must have been travelling to and from the area 100 years ago, especially in the height of winter!

Yet upon reaching this quaint little village, which was settled high up in the Dales, we soon stumbled across a small churchyard which contained the resting place of my great-great-grandparents, Thomas Marshall (d.1902), his wife Jane (d.1927), and their son William. Although this collapsed headstone would mean nothing to most people, finding the grave of my ancestors, and paying my respects to them in the village where they lived and loved was a spine-tingling moment. I believe my great-grandmother is in the churchyard too, although legend has it that the tumultuous Yorkshire weather may have carried her just beyond the graveyard wall!

It not only makes you feel closer to the past, but also closer to your family heritage. Years after their deaths, I think Thomas Marshall and his family appreciated the fact that their descendants came to remember them. I little soppy I know, but I’m interested to know whether you felt this way when researching your own family tree?

With strong family connections to the area, I grew up hearing stories of Pendle Hill and the infamous Pendle Witches. In August 1612, ten witches (8 women and 2 men) were tried and found guilty of witchcraft at Lancaster Castle. Condemned to death, the ten prisoners were transported back to their home within the shadow of Pendle Hill, where they were hanged and later buried in unmarked graves.

Despite being poor, illiterate and condemned, the legacy of the Pendle Witches has transcended through time and continues to define the modern-day Pendle communities. The lives, trials and deaths of Elizabeth Southerns, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Alizon Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redferne, John and Jane Bulcock, Katherine Hewitt, Margaret Pearson, Isabel Roby, and Alice Nutter attracts thousands of tourists today, and invigorates many locals. (You may have noticed that I named more than ten witches - this will be explained!). Today, many travel to Pendle Hill to walk in the footsteps of the infamous witches, and hear tales of their wicked misdeeds. They marvel at the statues which pay tribute to the condemned; count the many signs and street names honouring their memory, and step into local shops with shelves stacked high with witchy memorabilia.

So who were these infamous Pendle Witches? In the early 1600s, Lancashire was considered an isolated, backwards county far away from London. It was believed by contemporaries to be a place of tradition, superstition, rural isolation and simmering religious and political tensions. Furthermore, it was thought to house many recusant Catholics and maintain heretical Catholic beliefs. In the aftermath of the failed Gunpowder Plot in 1605, where Catholics aimed to blow up the Houses of Parliament and the political Protestant elite, Catholicism was largely viewed as a dangerous threat in 17th century England.

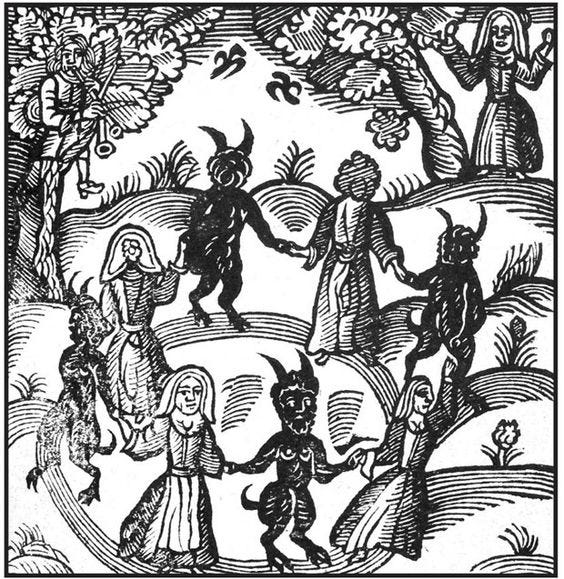

On top of all this, fears surrounding witchcraft were widespread. Malevolent magic was thought to be wielded by evil sinners associated with the devil. Mostly women and vulnerable members of society, these evil people were said to harm cattle, inflict pain and illness, and even commit murder through witchcraft, either as revenge against those who had wronged them, or to better themselves. Within this highly-religious age where witchcraft was a crime punishable by death, it was every Christians’ God-given duty to hunt down, punish, and eradicate witches from society.

By the early-17th century, two rival families headed by two elderly matriarchs, were feared to be witches operating within the settlements surrounding Pendle Hill. For decades, the two matriarchs, Elizabeth Southerns (alias Demdike) and Anne Whittle (alias Chattox), sought to make a living as ‘cunning women’. Poverty stricken and fighting for survival, Demdike, Chattox, and their families, were employed by the locals for their magical abilities, such as healing the sick, aiding injured cattle, finding lost possessions, or even inflicting harm upon enemies. Cunning folk like Demdike and Chattox used charms and prayers for their work, which sounded very similar to the old Catholic traditions which were now considered heretical in Protestant England. As they operated within the same communities and fought over the same potential customers, it’s unsurprising that Chattox and Demdike grew to dislike each other.

This rivalry filtered down into other members of Demdike’s and Chattox’s families too. For instance, Chattox’s youngest daughter Bessie broke into Demdike’s home of Malkin Tower and stole a considerable amount of goods. Bessie later flaunted her newfound possessions in from of Demdike’s family, much to their chagrin. When the two families found themselves under interrogation on charges of witchcraft, they quickly accused each other of performing sinful, criminal acts.

In March 1612, Demdike’s granddaughter Alizon Device was walking through a forest. Like most days, Alizon set out to beg for alms in the hope of raising enough money to feed herself and her family, especially her elderly grandmother Demdike, who was in her eighties by this time, increasingly frail and losing her sight. During her walk Alizon encountered a pedlar named John Law. She asked Law for some pins which he refused to give her. It’s likely that Law rejected Alizon’s request because of her inability to pay him.

Angered by Law’s refusal, Alizon cursed the pedlar as he retreated further down the path. Moments later, John Law collapsed. Seeking shelter in a nearby alehouse, John Law found himself unable to move his left side and speaking became a challenge. In the advent of modern medicine, we know strongly speculate that John Law suffered a stroke. Yet in 1612, in the wake of Alizon’s rage, Law believed that he had fallen foul of Alizon’s witchcraft.

Alizon herself adamantly believed that she had cursed Law and caused his ailments. When she was later caught by John Law’s son Abraham, and brought before the pedlar to explain herself, Alizon broke down in tears and wailed heartfelt apologies. Explaining that she was at fault yet unable to cure John of his illness, Alizon soon found herself arrested by the local Justice of the Peace, Roger Nowell.

During her interrogation, several members of Alizon’s family were later arrested on charges of witchcraft, alongside Chattox and many of her relatives. The list of prisoners grew several days later, when Elizabeth Device (Alizon’s mother) hosted a Good Friday dinner at her home in Malkin Tower. Dining on stolen mutton, Elizabeth and her guests were reported to be witches; plotting with their familiars, (animals who persuaded witches to ally with the devil), to blow up Lancaster Castle and release their imprisoned loved ones. Echoing the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, the magistrate burst in on the meeting/coven and arrested many of the attendees. It wasn’t long before they were transported to Lancaster Castle, where they joined Alizon in a cramped, unsanitary cell to await trial.

So horrendous were the conditions at Lancaster Castle, that old Demdike passed away before her trial. Alizon must have been devastated, for the two were incredibly close.

After several weeks in the damp, dark and dingy cells, Alizon Device and the 10 other accused witches were shoved into the daylight to be tried. One of the accused was a woman called Alice Nutter, who was a surprising member of the accused standing before the court on charges of witchcraft. Alice was a wealthier gentlewoman and neighbour to Chattox and Demdike. It is unknown why she became embroiled in the 1612 witchcraft case. It’s suspected that she may have harboured Catholic beliefs, as two of her relatives were hanged as Catholic priests. Maybe she was being targeted by ambitious Protestant magistrates, who hoped to undermine powerful Catholic families in the local area? Or maybe Alice attended in the Good Friday meeting as a concerned neighbour, hoping to provide aid and moral support to a family who had been torn apart by witchcraft accusations and imprisonment, only to be caught up in the later arrests? Alice herself may have known why she was targeted during the 1612 witchcraft trials, for she remained silent throughout her interrogation and maintained her innocence throughout. Perhaps she didn’t want to give her enemies the satisfaction of seeing her pleading for her life?

Shockingly, Alizon’s own 9-year-old sister appeared as the star witness against the accused. Young Jennet Device is a bit of an enigma. No one knows why she provided testimonies against her own family. Maybe she was intimidated by her social superiors? Maybe she was trying to save her own skin? Or maybe she sought revenge upon a family who treated this illegitimate child as an outcast?

Who knows.

All we know for sure, is that Jennet’s evidence against her family and their associates, proved to be their downfall. Standing up on a table in the courtroom, Jennet called the accused witches; stating that they conversed with the familiars on how to murder their enemies, and boasted previous killings to fellow guests at the Good Friday meeting. Her mother, Elizabeth Device, was so distraught at her daughter’s role in the trial, that she had to be removed.

Although children’s testimonies were allowed in court prior to this case, Jennet’s account proved to be vital to the prosecution. On the words of a 9-year-old girl, ten of the accused witches were found guilty and sentenced to death, including Jennet’s own mother, brother and sister. On 20th August 1612, the ten condemned witches were carted to Gallows Hill in Lancashire, where they were hanged.

Four hundred years later, and the memory of the Pendle Witches lingers over the dark, looming mound that is Pendle Hill. When before they inspired hatred, fear and derision, now the ten accused attract widespread admiration, awe and fascination. I myself have long been intrigued by their stories and the continued influence they have over modern-day Pendle. I only hope to discover more about this incredible tale of witchcraft, and the ‘witches’ who dominate it, in the hope of doing their memories justice after so much injustice was served to them during the awful summer of 1612.

Compelling article very well told. Thanks!

I can absolutely relate on the ancestry and have plans to someday visit the graves of ancestors I tracked down from New England, to Ireland, England and Germany. I think about them often and really enjoy finding old pictures sent in by distant relatives I’ve never met but am connected to through one person or another on Ancestry.

I really enjoyed the article as well! It’s such a dark history, like a scary movie you can’t bare to watch but feel compelled because these women’s stories must be told and remembered.